Victorian

Schools

Victorian

Schools

Schools

There were several kinds

of school for poorer children. The youngest might go to a "Dame" school,run

by a local woman in a room of her house. The older ones went to a day school.

Other schools were organised by churches and charities. Among these were

the "ragged" schools which were for orphans and very poor children.

School

room The school could be quite a grim building.

The rooms were warmed by a single stove or open fire. The walls of a Victorian

schoolroom were quite bare, except perhaps for an embroidered text. Curtains

were used to divide the schoolhouse into classrooms. The shouts of several

classes competed as they were taught side by side. There was little fresh

air because the windows were built high in the walls, to stop pupils

looking outside and being distracted from their work. Many schools were

built in the Victorian era, between 1837 and 1901. In the country you would

see barns being converted into schoolrooms. Increasing numbers of children

began to attend, and they became more and more crowded. But because school

managers didn’t like to spend money on repairs, buildings were allowed

to rot and broken equipment was not replaced.

School

room The school could be quite a grim building.

The rooms were warmed by a single stove or open fire. The walls of a Victorian

schoolroom were quite bare, except perhaps for an embroidered text. Curtains

were used to divide the schoolhouse into classrooms. The shouts of several

classes competed as they were taught side by side. There was little fresh

air because the windows were built high in the walls, to stop pupils

looking outside and being distracted from their work. Many schools were

built in the Victorian era, between 1837 and 1901. In the country you would

see barns being converted into schoolrooms. Increasing numbers of children

began to attend, and they became more and more crowded. But because school

managers didn’t like to spend money on repairs, buildings were allowed

to rot and broken equipment was not replaced.

Teachers

Children were often scared

of their teachers because they were very strict. Children as young as thirteen

helped the teacher to control the class. These “pupil teachers” scribbled

notes for their lessons in books .They received certificates which helped

them qualify as teachers when they were older. In schools before 1850 you

might see a single teacher instructing a class of over 100 children with

help of pupils called “monitors”. The head teacher quickly taught these

monitors, some of them as young as nine, who then tried to teach their

schoolmates. Salaries were low, and there were more women teaching

than men. The pale, lined faces of older teachers told a story. Some taught

only because they were too ill to do other jobs. The poor conditions in

schools simply made their health even worse. Sometimes, teachers were attacked

by angry parents. They shouted that their children should be at work earning

money, not wasting time at school. Teachers in rough areas had to learn

to box!

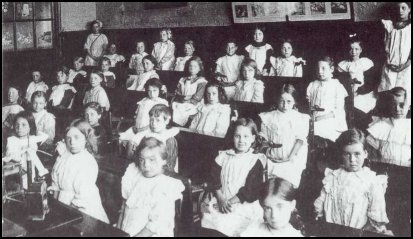

Pupils

After

1870, all children from five to thirteen had to attend school by law. In

winter in the countryside, many children faced a teeth chattering walk

to school of several miles. A large number didn’t turn up. Lessons lasted

from 9am to 5pm, with a two hour lunch break. Because classes were so large,

pupils all had to do the same thing at the same time. The teacher barked

a command, and the children all opened their books. At the

second command they began copying sentences from the blackboard. When pupils

found their work boring, teachers found their pupils difficult to control.

After

1870, all children from five to thirteen had to attend school by law. In

winter in the countryside, many children faced a teeth chattering walk

to school of several miles. A large number didn’t turn up. Lessons lasted

from 9am to 5pm, with a two hour lunch break. Because classes were so large,

pupils all had to do the same thing at the same time. The teacher barked

a command, and the children all opened their books. At the

second command they began copying sentences from the blackboard. When pupils

found their work boring, teachers found their pupils difficult to control.

Lessons

Victorian lessons concentrated

on the “three Rs”-Reading, wRiting and aRithmetic. Children learnt by reciting

things like parrots, until they were word perfect. It was not an exciting

form of learning! Science was taught by “object lesson”. Snails, models

of trees, sunflowers , stuffed dogs, crystals, wheat or pictures of elephants

and camels were placed on each pupil’s desk as the subject for the lesson.

The object lesson was supposed to make children observe, then talk about

what they had seen. Unfortunately, many teachers found it easier to chalk

up lists describing the object, for the class to copy. Geography meant

yet more copying and reciting - listing the countries on a globe, or chanting

the names of railway stations between London and Holyhead. If you

look at a timetable from late in the 1800s and you will see a greater number

of subjects, including needlework, cookery and woodwork. But the teacher

still taught them by chalking and talking.

Slates

and copybooks

Slates

and copybooks

Children learned to write

on slates, they scratched letters on them with sharpened pieces of slate.

Paper was expensive, but slates could be used again and again. Children

were supposed to bring sponges to clean them. Most just spat on the slates,

and rubbed them clean with their sleeves. Older children learned to use

pen and ink by writing in “copybooks”. Each morning the ink monitor filled

up little, clay ink wells and handed them round from a tray. Pens were

fitted with scratchy, leaking nibs, and children were punished for spilling

ink which “blotted their copybooks”. Teaches also gave dictation, reading

out strange poems which the children had to spell out correctly.

Reader

Slates showing pictures

and names of different objects hang from the walls of the infants class.

The children chant the name of each object in turn. When they can use these

words in sentences they will move on to a “reader”. This would p probably

be the Bible. For reading lessons, the pupils lined up with their toes

touching a semi-circle chalked on the floor. They took it in turns to read

aloud from the bible. The words didn’t sound like everyday words, children

stumbled over the long sentences. Quicker readers fidgeted as they waited

for their turn to read. School inspectors slowly realised that the bibles

language was too difficult. Bibles were gradually replaced by books of

moral stories, with titles like Harriet and the Matches. A reader had to

last for a whole year. If the class read it too quickly, they had to go

back to the beginning and read it all over again!

Abacus

The pupils used an abacus

to help them with their maths. Calculations were made using imperial weights

and measures instead of our simpler metric system. Children had to pass

inspections in maths, reading and writing before they could move up to

the next class or “standard”. Teachers were also tested by the dreaded

inspector, to make sure that they deserved government funds.

Cane

Teachers handed out regular

canings. Look inside the “punishment book” that every school kept, and

you will see many reasons for these beatings: rude conduct, leaving the

playground without permission, sulkiness, answering back, missing Sunday

prayers, throwing ink pellets and being late. Boys were caned across their

bottoms, and girls across their hands or bare legs. Some teachers broke

canes with their fury, and kept birch rods in jars of water to make them

more supple. Victims had to chose which cane they wished to be beaten with!

Dunce's

Cap

Dunce's

Cap

Punishment did not end

with caning. Students had to stand on a stool at the back of the class,

wearing an arm band with DUNCE written on it. The teacher then took a tall,

cone-shaped hat decorated with a large “D”, and placed it on the boys head.

Today we know that some children learn more slowly than others. Victorian

teachers believed that all children could learn at the same speed, and

if some fell behind then they should be punished for not trying hard enough.

Drill

When its time for PE

or “drill”, a pupil teacher starts playing an out-of-tune piano . The children

jog, stretch and lift weights in time to the awful music. It is like

a Victorian aerobics class! Even when the teacher rings a heavy , brass

bell to announce the end of school, the pupils march out to the playground

in perfect time

Playtime

Outside the classroom

is a small yard crowded with shrieking schoolmates. Games of blind mans

buff, snakes and ladders, hide-and-seek and hopscotch are in full swing.

Some boys would beg a pigs bladder from the butcher, which they would blow

up to use as a football. Others drilled hob nails through cotton reels

to make spinning tops.