|

|

To find out, first we looked at books in the library. That told us some of the things we wanted to know, but not everything. So, we sent an email to the webmaster. Here is our question.

|

|

"We have been looking in books in our library to find out how a satellite phone works. We have found that they use microwaves, and signals are bounced up to a geostationary satellite. If the satellite is over Tanzania, how does the message get to Dallas, because it is round the other side of the world? Does it bounce to another satellite above you? We would be very grateful if you could tell us. From Sasha, Gabrielle, Ritik, Jared, Kurt, Tamatoa and Scott. |

Here is the answer!

|

The team in Tanzania is carrying a very small satellite phone. It looks like, and opens like, a briefcase. The telephone is inside the case. The outside of the case is actually the antenna, which allows the phone to send and receive messages to satellites overhead. The message is sent in very short radio waves, called microwaves, and it goes to a satellite that stays in the same position over the earth's surface all the time. (This kind of orbit is called a geostationary orbit.) The particular satellites they are using are operated by Inmarsat, and they look like the photo on the right. |

|

|

|

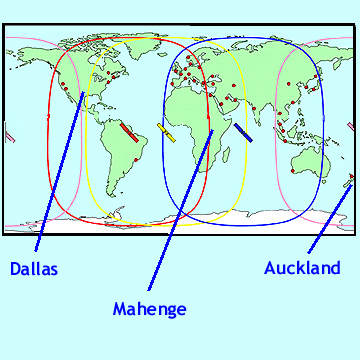

This diagram shows each satellite (the little coloured rectangles) with an oval area around each one in the same colour. The oval area shows the parts of the earth below that can send and receive to that particular satellite. The team in Mahenge have been using both the yellow one and the blue one. When the signal they send bounces up to the satellite, it is then sent down to a Land Earth Station, which transfers the signal on to the ordinary telephone system that goes round the world. It is just like a normal phone call to another country over telephone lines. The team leaves their photos and email messages in a folder on an internet server (which is just a big computer), and they pick up the ones other people send them at the same time. |